CHAPTER 2 CRY “HAVOC!” AND LET SLIP THE DOGS OF WAR

The result is a White House memoir that is the most comprehensive and substantial account of the Trump Administration, and one of the few to date by a top-level official. With almost daily access. Fifteen Years A Deplorable: A White House Memoir - Kindle edition by McCormick, Mike. Download it once and read it on your Kindle device, PC, phones or tablets. Use features like bookmarks, note taking and highlighting while reading Fifteen Years A Deplorable: A White House Memoir. 1 day ago What happened to the auctions for White House memoirs with little more than a few juicy tidbits dished up over poached salmon in Manhattan? To three midday glasses of. The Room Where It Happened: A White House Memoir. More Readouts in Books & Ideas. Betasat driver download. SELECTION FROM Every Day Is a Gift Tammy Duckworth.

15 Years A Deplorable: A White House Memoir by Mike McCormick. Amazon Reviews Matter! Pulling no punches, former White House stenographer Mike McCormick describes with eyewitness precision specific transgressions and why those transgressors should.

On Saturday, April 7, 2018, Syrian armed forces, using chemical weapons, attacked the city of Douma in southwest Syria and other nearby locations. Initial reports had perhaps a dozen people killed and hundreds wounded, including children, some grievously sickened by the dangerous chemicals.1 Chlorine was the likely base material for the weapons, but there were claims of sarin gas activity and perhaps other chemicals.2 Bashar al-Assad’s regime had similarly used chemical weapons, including sarin, one year earlier, on April 4, 2017, at Khan Shaykhun in northwest Syria. Only three days later, the United States responded forcefully, launching fifty-nine cruise missiles at the suspected site from which the Syrian attack emanated.3

Syria’s dictatorship obviously had not learned its lesson. Deterrence had failed, and the issue now was how to respond appropriately. Unhappily, a year after Khan Shaykhun, Syria policy remained in disarray, lacking agreement on fundamental objectives and strategy.4 Now it was again in crisis. Responding to this latest Syrian chemical-weapons attack was imperative, but we also urgently needed conceptual clarity on how to advance American interests long-term. An NSC meeting held the week before Douma, however, pointed in exactly the opposite direction: US withdrawal from Syria. Leaving would risk losing even the limited gains achieved under Barack Obama’s misbegotten Syria-Iraq policies, thereby exacerbating the dangers his approach fostered. Responsibility for this policy disarray, one year after Khan Shaykhun, rested at that iconic location where the buck stops: the Resolute desk in the Oval Office.

At about nine a.m. on April 8, in his own personal style and the style of our times, Donald J. Trump, President of the United States of America, tweeted:

Many dead, including women and children, in mindless CHEMICAL attack in Syria. Area of atrocity is in lockdown and encircled by Syrian Army, making it completely inaccessible to outside world. President Putin, Russia and Iran are responsible for backing Animal Assad. Big price…

…to pay. Open area immediately for medical help and verification. Another humanitarian disaster for no reason whatsoever. SICK!

Minutes later, he tweeted again:

If President Obama had crossed his stated Red Line In The Sand, the Syrian disaster would have ended long ago! Animal Assad would have been history!

These were clear, forceful statements, but Trump tweeted before consulting his national security team. Lieutenant General H. R. McMaster, my predecessor as National Security Advisor, had left Friday afternoon, and I didn’t start until Monday. When I tried to pull together a meeting on Sunday, White House lawyers blocked it, because I would not officially become a government employee until Monday. This gave the word “frustration” new meaning.

Trump called me Sunday afternoon, and we (mostly he) talked for twenty minutes. He mused that getting out of the Middle East the right way was tough, a theme he raised repeatedly during the call, interspersed with digressions on trade wars and tariffs. Trump said he had just seen Jack Keane (a four-star general and former Army Vice Chief of Staff) on Fox News and liked his idea of destroying Syria’s five main military airfields, thereby essentially knocking out Assad’s entire air force. Trump said, “My honor is at stake,” reminding me of Thucydides’s famous observation that “fear, honor and interest” are the main drivers of international politics and ultimately war. French President Emmanuel Macron had already called to say France was strongly considering participating in a US-led military response.5 Earlier in the day, presidential son-in-law Jared Kushner had told me that UK Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson had phoned him to relay essentially the same message from London. These prompt assurances of support were encouraging. Why a foreign minister was calling Kushner, however, was something to address in coming days.

Trump asked about an NSC staffer I planned on firing, a supporter of his since the earliest days of his presidential campaign. He wasn’t surprised when I told him the individual was part of “the leak problem,” and he continued, “Too many people know too many things.” This highlighted my most pressing management problem: dealing with the Syria crisis while reorienting the NSC staff to aim in a common direction, a bit like changing hockey lines on the fly. This was no time for placid reflection, or events would overtake us. On Sunday, I could only “suggest” to the NSC staff that they do everything possible to ascertain all they could about the Assad regime’s actions (and whether further attacks were likely), and develop US options in response. I called an NSC staff meeting for six forty-five a.m. Monday morning to see where we stood, and to assess what roles Russia and Iran might have played. We needed decisions that fit into a larger, post-ISIS Syria/Iraq picture, and to avoid simply responding “whack-a-mole” style.

I left home with my newly assigned Secret Service protective detail a little before six a.m., heading to the White House in two silver-colored SUVs. Once at the West Wing, I saw that Chief of Staff John Kelly was already in his first-floor, southwest-corner office, down the hall from mine on the northwest corner, so I stopped by to say hello. Over the next eight months, when we were in town, we both typically arrived around six a.m., an excellent time to sync up as the day began. The six forty-five NSC staff meeting confirmed my—and what seemed to be Trump’s—belief that the Douma strike required a strong, near-term military response. The US opposed anyone’s use of WMD (“weapons of mass destruction”)—nuclear, chemical, and biological—as contrary to our national interest. Whether in the hands of strategic opponents, rogue states, or terrorists, WMD endangered the American people and our allies.

A crucial question in the ensuing debate was whether reestablishing deterrence against using weapons of mass destruction inevitably meant greater US involvement in Syria’s civil war. It did not. Our vital interest against chemical-weapons attacks could be vindicated without ousting Assad, notwithstanding the fears of both those who wanted strong action against his regime and those who wanted none. Military force was justified to deter Assad and many others from using chemical (or nuclear or biological) weapons in the future. From our perspective, Syria was a strategic sideshow, and who ruled there should not distract us from Iran, the real threat.

I called Defense Secretary Jim Mattis at 8:05 a.m. He believed Russia was our real problem, harking back to Obama’s ill-advised 2014 agreement with Putin to “eliminate” Syria’s chemical weapons capability, which obviously hadn’t happened.6 And now here we were again. Unsurprisingly, Russia was already accusing Israel of being behind the Douma strike. Mattis and I discussed possible responses to Syria’s attack, and he said he would be supplying “light, medium, and heavy” options for the President’s consideration, which I thought was the right approach. I noted that, unlike in 2017, both France and Britain were considering joining a response, which we agreed was a plus. I sensed, over the phone, that Mattis was reading from a prepared text.

Afterward, UK national security advisor Sir Mark Sedwill called me to follow up Johnson’s call to Kushner.7 It was more than symbolic that Sedwill was my first foreign caller. Having our allies more closely aligned to our main foreign-policy and defense objectives strengthened our hand in critical ways and was one of my top policy goals. Sedwill said deterrence had obviously failed, and Assad had become “more adept at concealing his use” of chemical weapons. I understood from Sedwill that Britain’s likely view was to ensure that our next use of force was both militarily and politically effective, dismantling Assad’s chemical capabilities and re-creating deterrence. That sounded right. I also took a moment to raise the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, even in the midst of the Syria crisis, emphasizing the likelihood, based on my many conversations with Trump, that America now really would be withdrawing. I emphasized that Trump had made no final decision, but we needed to consider how to constrain Iran after a US withdrawal and how to preserve trans-Atlantic unity. Sedwill was undoubtedly surprised to hear this. Neither he nor other Europeans had heard it before from the Administration, since, before my arrival, Trump’s advisors had almost uniformly resisted withdrawal. He took the point stoically and said we should talk further once the immediate crisis was resolved.

At ten a.m., I went down to the Situation Room complex for the scheduled Principals Committee meeting of the National Security Council, a Cabinet-level gathering. (Old hands call the area “the Sit Room,” but millennials call it “Whizzer,” for the initials “WHSR,” “White House Situation Room.”) It had been completely renovated and much improved since my last meeting there in 2006. (For security reasons as well as efficiency, I later launched a substantial further renovation that began in September 2019.) I normally would chair the Principals Committee, but the Vice President decided to do so, perhaps thinking to be helpful on my first day. In any case, I led the discussion, as was standard, and the issue never arose again. This initial, hour-long session allowed the various departments to present their thoughts on how to proceed. I stressed that our central objective was to make Assad pay dearly for using chemical weapons and to re-create structures of deterrence so it didn’t happen again. We needed political and economic steps, as well as a military strike, to show we had a comprehensive approach and were potentially building a coalition with Britain and France. (UK, US, and French military planners were already talking.)8 We had to consider not just the immediate response but what Syria, Russia, and Iran might do next. We discussed at length what we did and didn’t know regarding Syria’s attack and how to increase our understanding of what had happened, especially whether sarin nerve agent was involved or just chlorine-based agents. This is where Mattis repeated almost verbatim his earlier comments, including that the Pentagon would provide a medium-to-heavy range of options.

Further work on Syria, not to mention filling out more government forms, swirled along until one p.m., when I was called to the Oval. UN Ambassador Nikki Haley (who had participated in the Principals Committee via secure telecommunications from New York) was calling to ask what to say in the Security Council that afternoon. This was apparently the normal way she learned what to do in the Council, completely outside the regular NSC process, which I found amazing. As a former UN Ambassador myself, I had wondered at Haley’s untethered performance in New York over the past year-plus; now I saw how it actually worked. I was sure Mike Pompeo and I would be discussing this issue after he was confirmed as Secretary of State. The call started off, however, with Trump asking why former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, before he left office, had approved $500 million in economic assistance to Africa. I suspected this was the amount approved by Congress in the course of the appropriations process, but said I would check. Trump also asked me to look into a news report on India’s purchasing Russian S-400 air defense systems because, said India, the S-400 was better than America’s Patriot defense system. Then we came to Syria. Trump said Haley should basically say, “You have heard the President’s words [via Twitter], and you should listen.” I suggested that, after the Security Council meeting, Haley and the UK and French Ambassadors jointly address the press outside the Council chamber to present a united front. I had done that many times, but Haley declined, preferring to have pictures of her alone giving the US statement in the Council. That told me something.

In the afternoon, I met with NSC staff handling the Iran nuclear-weapons issue, asking them to prepare to exit the 2015 deal within a month. Trump needed to have the option ready for him when he decided to leave, and I wanted to be sure he had it. There was no way ongoing negotiations with the UK, France, and Germany would “fix” the deal; we needed to withdraw and create an effective follow-on strategy to block Iran’s drive for deliverable nuclear weapons. What I said couldn’t have been surprising, since I had said it all before publicly many times, but I could feel the air going out of the NSC staff, who until then had been working feverishly to save the deal.

I was back in the Oval at four forty-five p.m. for Trump to call Macron.9 I typically joined in the President’s calls with foreign leaders, which had long been standard practice. Macron reaffirmed, as he was doing publicly, France’s intention to respond jointly to the chemical attacks (and which, after the fact, he actually took credit for!).10 He noted UK Prime Minister Theresa May’s desire to act soon. He also raised the attack earlier on Monday against Syria’s Tiyas airbase, which housed an Iranian facility, and the risk of Iran’s counterattacking even as we planned our own operations.11 I spoke later with Philippe Étienne, my French counterpart and Macron’s diplomatic advisor, to coordinate carrying out the Trump-Macron discussions.

As I listened, I realized that if military action began by the weekend, which seemed likely, Trump couldn’t be out of the country.12 When the call ended, I suggested he skip the Summit of the Americas conference in Peru scheduled for that time and that Pence attend instead. Trump agreed, and told me to work it out with Pence and Kelly. When I relayed this to Kelly, he groaned because of the preparations already made. I responded, “Don’t hate me on my first day,” and he agreed a switch was probably inevitable. I went to the VP’s office, which was between my office and Kelly’s, to explain the situation. While we were talking, Kelly came in to say the FBI had raided the offices of Michael Cohen, a Trump lawyer and chief “fixer” for nondisclosure agreements with the likes of Stormy Daniels, not exactly a matter of high state. Nonetheless, in the time I spent with Trump the rest of the week, which was considerable, the Cohen issue never came up. There was no trace of evidence to suggest Cohen was on Trump’s mind, in my presence, other than when he responded to the incessant press questioning.

On Monday evening, Trump hosted a semiannual dinner with the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the military combatant commanders to discuss matters of interest. With all of them in town, it also provided an opportunity to hear their views on Syria. Had this not been my first day, with the Syria crisis overshadowing everything, I would have tried to meet them individually to discuss their respective responsibilities. That, however, would have to wait.

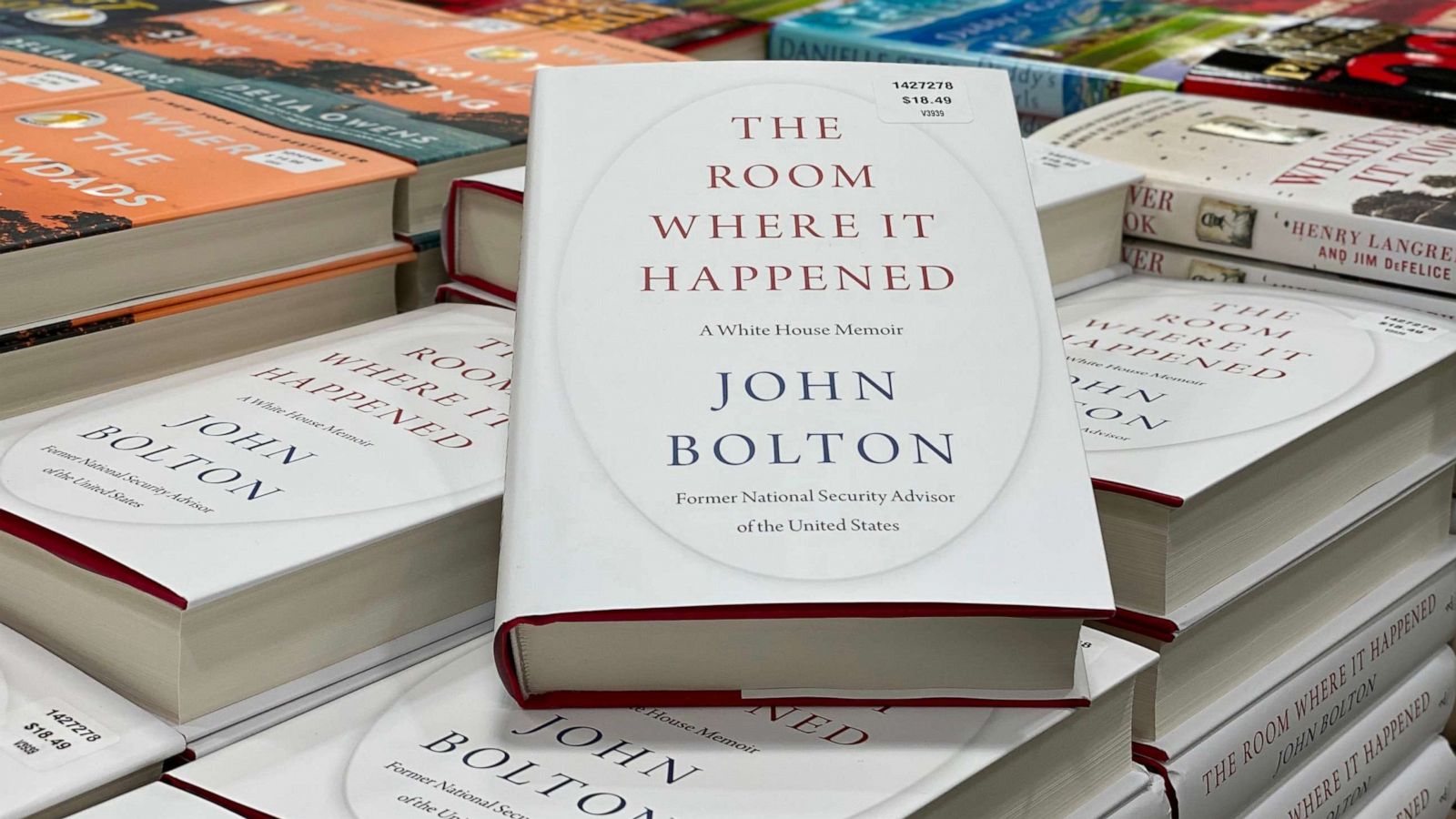

- By John Bolton

- Simon & Schuster

- 592 pp.

- Reviewed by Salley Shannon

- July 1, 2020

This eagerly awaited tell-all is over-detailed, ironic, and believable.

A little sympathy for John Bolton, please. The odor of skunk clings to him, and it’s possible that only the milk bath of history will be curative.

Democrats call the former national security advisor to President Donald Trump a traitor because he didn’t testify during the impeachment hearings, although his underlings did. His tell-all book and its $2 million advance offend them.

Republicans, and especially Trump-leaning Republicans, label Bolton a turncoat. Before his time in the White House, and certainly during it, man and mustache frequently appeared on Fox News. Now, his tell-all book and its $2 million advance offend them.

Future historians are going to canonize the man.

In The Room Where It Happened, Bolton lays before us in near-stifling detail some 17 months of life in the Trump White House. The policy disputes, the infighting, the president who can’t be briefed on world events because he already knows everything.

Descriptions of the lead-ups to historic events, such as the meeting with North Korea’s Kim Jong-un in the DMZ, by themselves will be invaluable. That episode, incidentally, was precipitated by a tweet, although Trump said it was Kim’s idea. “All “risky theatrics, in my view, not substance,” Bolton tells us.

Bolton is not a graceful writer, but he’s a clear, competent one and, occasionally, a witty one. Of course, the telling is slanted toward what Bolton thinks should have happened, and oh the pity it didn’t. No sin in that. Such defines the genre.

Although Bolton’s exasperation often is obvious, there’s relatively little of the score-settling almost requisite to political memoirs. When it turns up, it’s most often as an aside: G7 meetings are like “self-licking ice cream cones.”

He is a master at pointing out inadvertently funny or ironic situations without saying, “Can you believe this?” Trump, at a banquet in Japan, remarks that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s father, a kamikaze pilot during WWII, was disappointed he hadn’t succeeded in that role. Writes Bolton: “If he had been, Abe, born in 1954, wouldn’t exist. Mere historical details.”

During the same visit, the president had trouble staying awake during a meeting with Abe. “He never fell out of his chair…but he was, in the immortal words of one of my Fort Polk drill sergeants, ‘checking his eyelids for pin holes.’”

Bolton does throw a few serious punches. Many are directed at then Secretary of Defense James Mattis, who, in his telling, slow-walks presenting military responses when the president (and Bolton) asks they be among a range of options. Mattis delays “to the last minute, to have things come out as he wants.” Mattis, he continues, is “a classic bureaucrat” who plays with “marked cards.”

John Bolton has been in public life for four decades. As the saying goes, takes one to know one.

His job, Bolton says, was “like making and executing policy inside a pinball machine, not the West Wing of the White House.”

Throughout the book, Bolton makes no secret of his growing disdain for the way this White House operates, or for the man in charge. Minecraft xbox. He does it by building detail upon detail to show us what was going on, and using Trump’s own words.

That said, the best-known hawk of his era doesn’t often disembowel. A pity, really. Such moments keep the pages turning.

Bolton is wicked smart and blessed with a prodigious memory. Unfortunately for readers, he also is like the storytelling uncle who drifts off into so much backstory and trivia that you want to hurl the gravy boat at his head. The same myriad layers of observation that will make historians giddy drove me to mutter out loud, “Get on with it! I don’t care about the 11 phone calls you made before noon on Tuesday!”

But all those layers do pack a wallop. What is most striking about The Room Where It Happened is how the weight and volume of what he tells us, the names of people present, what they said, what President Trump and his highest-ranking minions said and did, what happened as a result — witness multiple reports here and abroad — eventually outrun Bolton’s own bona fides.

Whether or not Bolton is motivated by self-justification, and whether you were a hawk or a dove when you picked up the book, become irrelevant.

We can only guess how his testimony before Congress would have gone. On the whole, the testimony in this book is convincing. (The ideologue in either direction will, of course, disagree.)

It’s a tough read. In his ending remarks, Bolton notes that the action government censors most often mandated was “take out the quotation marks.” Generally, doing that was enough to satisfy them. The actual words attributed to people stayed the same. One can discern a little glee as Bolton complies, so no harm was done.

But graceful writing, or the lack thereof, and the graphic design of a book do matter. The Room Where It Happened can be riveting. Most often, it is not. With the sad weight of the content, plus no “he said” and “she observed” quotations to give the eye relief as long, grey paragraphs march across the pages, there were times I pushed myself to keep reading.

But worth it? You bet. Of all the Trump-era tell-alls to date, this one is a gut punch.

Salley Shannon's writing has appeared in many national magazines and newspapers.

How To Start A Memoir